Pōpō!: Level 3

Te Takenga Mai o Te Kūmara

This unit uses the third and fourth stanzas of the oriori Pōpō! as a focus for learning, and gaining a deeper understanding of the text. It links to the Reo Māori, Tikanga ā-Iwi and Hangarau learning areas, supporting teaching and learning at level 3 of Te Marautanga o Aotearoa.

The activities have been designed to create oral language opportunities – both formal and informal.

Pōpō!

Nā Enoka Te Pakaru i tito

(the third and fourth stanzas)

Kei te kukunetanga mai o Hawaiki

Ko te āhua ia.

Ko Māuiwharekino ka noho ia i a Pani

Ka kawea ki te wai o Monaariki

Nā one-hunga, nā one-rere

Nā te piere, nā te matata, te pia-tangi-wharau

Ka hoake ki runga rā te pīpīwharauroa

Nā Whena koe, e Waho e! I tuatahi, e Waho e!

Tuarua, ka topea i reira ko te whata-nui, ko te whata-roa

Ko te tīhaere nā Kohuru, nā Paeaki

Nā Rākaiora, nā Turiwhatu

Ko Waiho anake te tangata i rere noa i te ahi rara a Rongomaraeroa

Ko te kākahu nō Tū ko Te Rangikaupapa

Ko te tatua i riro noa i a Kanoa, i a Matuatonga

Tēnei te mānawa ka puritia, tēnei te mānawa ka tawhai

Kia haramai ana tōna hokowhitu i te ara

Akoranga 1

Whakarongo, Kōrero

Purpose

To introduce, listen to, and discuss the mōteatea Pōpō with students.

Learning Intentions

Students are learning:

- To recite the first three stanzas of the oriori Pōpō

- That Pōpō! is an oriori – a mōteatea composed to pass on important tribal histories.

What You Need

- Pōpō! – Animated mōteatea

- Data projector or interactive whiteboard

What You Do

Akoranga ā-Akomanga

Teach first thing in the morning. The following material is designed to be spread over a number of sessions – break it up where it suits you and your students.

Listening to Pōpō!

- Use the audio track of Pōpō!. Ask your students to lie down and close their eyes. Play the audio track and listen to the entire mōteatea.

- After listening to Pōpō! ask these questions:

What feelings did you get when you listened to this moteatea?

Did anything happen to you when you were listening?

- Talk about the moteatea. Explain:

Pōpō! is a Te Aitanga-a-Māhaki oriori, composed by Enoka Te Pakaru. It is thought this oriori was composed at least 400 years ago. This ancient and beautiful text is still being performed and is widely known.

Oriori were composed to impart important tribal knowledge to babies and children so that from a very young age they heard things like whakapapa, tribal histories, important tūpuna and origin stories. By repetition of these oriori over their early years, children grew up strong in the knowledge of who they were and where they came from.

Pōpō! retells many kōrero about how the kūmara came to the Tūranganui-a-Kiwa region.

- Play Pōpō! again, but this time show the pictures that go with the text. Listen to just the first four stanzas. Between stanzas brainstorm as class the key words they remember hearing. Record the words.

Possible list first stanza:

pōpō

Tama

Tangaroa

kūmara

tupuna

haruru

pakake

Uenuku

waiū

Possible list second stanza:

Uru

Ngangana

Te Aotū

Te Aohore

Hinetūāhōanga

Te Whatu o Poutini

Possible list third stanza:

Māui-wharekino

Pani

Te Wai o Monariki

Onehunga

Onerere

piere

matata

hoake

pīpīwharauroa

Whena

Waho

Possible list fourth stanza:

topea

Whatanui

Whataroa

Kohuru

Paeaki

Turiwhatu

Rākaiora

waiho

ahi rara a rongomaraeroa

kākahu nō Tū

Te Rangikaupapa

tātua

Kanoa

Matuatonga

manawa

hokowhitu

- Using the word lists, recap the main ideas and story lines with the class.

Stanza 1

Establishes that this is an oriori, to soothe the baby, Tama. It introduces Te Pouahaokai, a magical bird that is a kaitiaki of the people. It refers to Uenuku, a progenitor of the kūmara, and of the journey by Pourangahua across the oceans to retrieve the kūmara from Parinuiterā.

Stanza 2

Provides the whakapapa of Uru and Ngangana. It then introduces the original form of pounamu, Te Whatu o Poutini, and Hinetuahōanga who was the sandstone maiden (sandstone was used to shape and carve pounamu). There is a story that Ngahue fled Hawaiki with his pet fish called Poutini. Hinetuahōanga had been bothering the fish and she chased them to Mayor Island in the Bay of Plenty. Ngahue and Poutini escaped to the West Coast of the South Island, where Ngahue found a safe place in the Arahura River for Poutini to live in peace. The West Coast has since been known as Te Tai Poutini.

Stanza 3

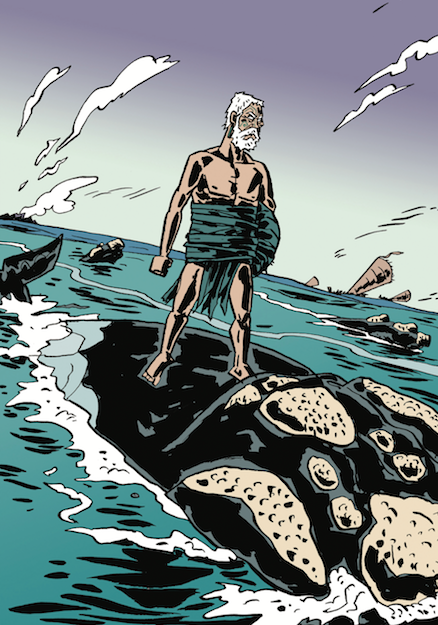

Introduces the story of Pani and her role as kaitiaki and progenitor of the kūmara. (The full story is told in this unit.)

Stanza 4

Introduces the second part of the oriori, which is mostly concerned with how Māori brought the kūmara to Aotearoa, and the rituals around its cultivation and harvest. The first part of the oriori was more focused on its origin.

When the kūmara arrived in Gisborne an altar was established where planting rituals were carried out. Special trees were felled to make posts for the altar. Snares were built to snare bad spirits (similar to those used for catching birds).

The text talks of people and atua:

– The sisters-in-law of Pourangahua.

– Rākaiora, a tohunga reknowned for his knowledge of the kūmara.

– Tūmatauenga and Rongomaraeroa – who are in constant opposition, existing to maintain a balance in life.

There is reference also to “ahi rara” – all the different hapū in the region.

Learning the oriori

- The next task is to learn the first four stanzas of Pōpō!. You could choose to learn these as a class or in small groups. Learn each stanza before moving to the next. You could retell the main ideas (above) of each stanza to introduce them. You could also use the images from the Pōpō! digital resource.

- Learn the stanzas line by line, adding a new line in when you are confident that students have embedded the previous lines. Depending on your students this may take a few sessions.

Supporting activities

Use these to help reinforce learning.

- Using the key word lists get the students to write the words onto cards, shuffle them and then try and order them – firstly, into the correct stanza, then in the order that they occur in the stanza.

- Cut the oriori into lines of texts that the students could then sequence. Give each group a different set of lines. Groups present their lines back to the whole class.

- Using the images from the first four stanzas as starters, ask the students to draw their favourite part of the oriori. Ask them to share their picture with a friend and tell them about their picture. Friends respond to their presentation and artwork.

He Huatau Aromatawai

Students can:

- Retell parts of the oriori in their own words.

- Can recite/perform the first 4 stanzas of the oriori Pōpō!

Akoranga 2

Tūmatauenga and Rongomaraeroa

Purpose

To explore the different parts of a pūrākau whakamārama.

Learning Intentions

Students are learning:

- To identify the different parts of a pūrākau whakamārama.

- To retell the story in video format.

What You Need

- Ko Wai – Pōpō! – Animated mōteatea

- Large sheets of paper and pens

- He Manu Tuhituhi – He Tuhinga Pūrākau Whakamārama/ He Whakamāramatanga o ngā Wāhanga[1]

- A device that has a movie camera

- The pūrākau A TŪMATAUENGA RĀUA KO RONGOMARAEROA-A2.PDF

- Images – PANI-WHAKAAHUA-A2.PDF

What You Do

Introduction

- Display an image or images from stanza 3 of Pōpō! In groups of five students talk about what they remember of the story, (using the image/s to prompt discussion).

- Explain that there are many different stories about the origins of kūmara. Ask what things they know already. Record a list.

Tūmatauenga and Rongomaraeroa

-

Explain:

Ko te pūtake o te pūrākau whakamārama he whakamārama i te takenga mai o ngā āhuatanga o te ao me te hua o aua āhuatanga ki te tangata. - Introduce the parts of a pūrākau whakamārama. Discuss each of these parts. (Pages 11–12 of He Tuhinga Pūrakau Whakamārama will help you with this.)

E rima ngā wāhanga o te pūrākau whakamārama:

1. Te tapanga.

2. Te tīmatanga.

3. Te whakatakinga.

4. Te raupapatanga mahi.

5. Te whakataunga.

- Introduce the story of Rongomaraeroa and Tūmatauenga and read to the class.

A Tūmatauenga rāua ko Rongomaraeroa

I ngā rā o nehe noa atu, tērā ētahi tāne tokorua, he tuakana teina, ko Tūmatauenga rāua ko Rongomaraeroa ō rāua ingoa. He māra kūmara tā rāua, ko Pōhutukawa te ingoa. He aha rā, ka ara ake he tohe, he whakatete i waenga i a rāua. Ka mea, ka kaha ake te riri, ka pakanga tonu rāua. Haere tupehu atu ana a Tūmatauenga ki roto rawa o te ngahere kia kite i a Rurutangiakau. Ko Rongomaraeroa, whakangaro atu ana ki te moana. I reira ka hoatu he taonga ki tēnā, ki tēnā. Ko te koha a Rurutangiakau ki a Tūmatauenga, ko tāna tama tonu, ko Akeakerautangi. E rua ngā māngai o Akeakerautangi, e rua anō ōna arero, ōna ihu, e whā ōna karu, e whā anō ōna taringa me ōna pongāihu. Koia tēnei ko te taiaha tuatahi ki te ao. Ko tā Tangaroa koha ki a Rongomaraeroa, ko tana tamāhine tonu, ko Merepounamu. Arā kē tōna ātaahua, tōna mātao, tōna kānapanapa, tōna kaha – ko te moana hoki tōna rite.

Hoki ake ana ngā tāne nei ki te kāinga, ka tū ko te pākanga e mōhiotia nei ko Moengatoto. Heoi anō, kīhai i puta he toa, ā, kua mau tonu mai te taukumekume, te kākari mutunga kore i waenga i te whawhai me te rangimārie hei pīkaunga mā tāua te tangata i muri iho.

Heoi anō, ka tūkaha tonu a Rongomaraeroa ki te tiaki i tana tino tamaiti, i te kūmara. Ka hunaia e ia ki roto rawa o te wahine nui puku nei, i a Pani. Noho ana ko Pani te rua o te kūmara i muri mai.

I ngā wā o te korekore, o te matekai, i ngā wā rānei o te pakanga, kua tata kore ngā kai i ngā rua, ka tahuna e Pani te ahi tunu kai, ā, ka haere ki ngā wai e kīia nei ko Monariki. I reira, ka kuhu atu i te wai, ka toro ki roto anō i a ia, ka whakakī i tana kete ki te kūmara.

Hei te hokinga ki te kāinga, ka tunua aua kūmara, ka tohaina ki te iwi. Ka hia rangi rā pea, koinei tāna mahi, hei whāngai i te iwi.

Ka roa e pēnei ana, kua tīmata te uiui, te kōhumuhumu i waenga i ngā tāngata, pēnei nā, “I ahu mai ana i hea ēnei kūmara a Pani? Kua piango hoki te rua …”

I tētahi ahiahi i a Pani e wehe ana i te papa kāinga nei, ka whāia torohūtia e tētahi tangata, ko Patatai te ingoa. Kia kore ai ia e kitea e Pani, ka huri ia i tōna āhua kia rite ki tō te moho. Ko te moho, he manu hunahuna ka whakapupuni i te taha o te repo. Ka rere te moho nei ki te wai, ka mīharo i tāna i kite atu ai, ka puta ohorere te korowhio i tana korokoro. Me te aha, ohorere ana anō hoki ko Pani. Ka titiro atu te wahine ki te moho, ā, i tērā tonu, ka huri anō tana āhua ki tō te tāne. Nui atu te whakamā o Pani i kitea ia e te tāne nei e tango ana i te kūmara mai i roto tonu i a ia. Oma atu ana ki te kāinga me te tangi haere atu anō.

Mai i taua wā, ka tīmata te iwi, ngā tāngata katoa ki te āta tiaki, ki te āta whakatupu i te kūmara. Noho ana ko Pani te kaiwhakahaere i ngā karakia i te whakatōnga me te hauhakenga o te kūmara. Ka mau tonu te aroha o tana tāne, o Mauiwharekino ki a ia. Ā, ka roa rāua e noho ana i waenganui i te iwi, i runga i te pai, i te takaahuareka.

Identify parts of the pūrākau

- Using a large piece of paper and pens, students brainstorm what they heard using the framework in He Manu Tuhituhi – He Tuhinga Pūrākau Whakamārama/ He Whakamāramatanga o ngā Wāhanga.

1. Te tapanga.

2. Te tīmatanga.

3. Te whakatakinga.

4. Te raupapatanga mahi.

5. Te whakataunga.

- Once the groups feel they have their own versions of the story organised under the 5 sections, have them share their combined stories with the class by retelling of the story out loud. Students can each tell a part of the story.

- Give each student a copy of the pūrākau, or show it on the data projector. Ask them to make a flow chart where they complete the following:

The story outline

Te Tapanga

– He aha te tapanga o te pūrākau?

Te Tīmatanga

– Tuhia he kōwae e whakamārama ana i te tūāpapa o te pūrākau.

Te Whakatakinga

– Ko wai ngā atua matua?

– He aha tētahi āhuatanga o te mahi kei te haere?

Te Raupapatanga Mahi

– I pēhea te mahi i tīmata ai?

– I pēhea te mahi i tipu haere ai ki tōna teiteitanga?

– He aha tōna teiteitanga?

Te Whakataunga

– I pēhea te mahi i tau ai?

– He aha te hua i puta mai ki te ao?

– He aha te tikanga o te hua i puta ki te tangata?

- Using what they have written under each section, have them film themselves presenting a review of the story. Ask them to finish their presentation with a rating i.e. how many stars would you give the story? (1–5) ✪✪✪✪✪

He Huatau Aromatawai

Students can:

- Use a flow chart to Identify the different parts of the pūrākau.

- Retell and review the pūrākau in a video presentation.

Akoranga 3

Whakataukī, Whakatauākī rānei

Purpose

To explore some familiar whakataukī and whakatauākī and to understand the differences between the two.

Learning Intentions

Students are learning:

- To investigate whakataukī and whakatauakī and understand the difference between the two.

- The whakatauākī, ‘Waiho, mā te whakamā e patu.’

- To research whakataukī and create a back-story to a chosen whakataukī.

What You Need

- Large sheets of paper and pens

- Internet and library for research

- Copies of the whakataukī

What You Do

Whakataukī, whakatauākī – what do we know already?

Whakataukī and whakatauākī are short texts that over time have become widely used to describe different things, people, places or situations. They can use metaphor or simile, or simply sum up a situation in very few words.

– Whakatauākī are proverbs whose origin we know – we know who said it first and what the story is behind the saying.

– Whakataukī are proverbs that we know really well, but we don’t know the origin of, or how they came to be so widely used.

Waiho mā te whakamā e patu is a very well-known example of a whakatauākī. It was first uttered by Te Tahi-o-te-rangi, a powerful tohunga from Whakatāne. His people were very afraid of him and his power – they decided to try and get rid of him. They organized a tītī hunting expedition to Whakaari and asked Te Tahi-o-te-rangi to accompany them. The people worked during the night, using rama to catch the tītī and Te Tahi-o-te-rangi fell asleep. When he awoke in the morning he discovered that his people had left him stranded on the island.

The people were pleased with themselves, and imagined their lives to be so much better without the frightening old tohunga. However, Te Tahi-o-te-rangi had no intention of spending the rest of his days on Whakaari. He took three strands of harakeke from his magical belt and recited karakia to Tangaroa. A giant whale, Tūtarakauika, appeared and Te Tahi-o-te-rangi climbed on its back and was carried back the mainland.

Te Tahi-o-te-rangi returned to his home and as the people passed his house they were terrified that he would unleash a terrible curse upon them. Te Tahi-o-te-rangi looked at them disdainfully, as they cowered and bowed, and he uttered the words, “Waiho, mā te whakamā e patu.”

- Organise the students into small groups. Ask them to think about a whakataukī that they know already, or they could use one of the following.

– Kāore te kūmara e kōrero mō tōna māngaro.

– Ka hua kūmarahou, ka whakatō kūmara.

– He kōanga tangata tahi, he ngahuru puta noa.

– E tipu atu te kūmara, e ohu e te anuhe.

- Students work in pairs or individually. Get them to brainstorm what the whakataukī might mean and then create a backstory to the whakataukī.

Questions to help guide them could be:

– What is the proverb describing? (For example, beauty, laziness, kindness.)

– What is its tone?

– Is it a warning?

– Was is it describing e.g. beauty, laziness, kindness?

- Students share their whakataukī and back-stories.

Possible Assessment Opportunities

- Students think about something they have felt strongly about recently and make up their own whakataukī. Share them with the class.

- Make an audio book of whakataukī and their origins.

Akoranga 4

Tohunga Tunukai

Purpose

To participate in Māori Masterchef – where kūmara is the star ingredient.

Learning Intentions

Students are learning:

- To manage time and work cooperatively.

- To think creatively and competitively.

- To cook and present a dish using limited ingredients, equipment and time.

What You Need

- For each work station:

– kūmara – medium sized

– salt

– oil

– dried or fresh herbs

– garlic

– spices

– tomato puree

– sour cream

– sugar

– A3 sheet of cardboard

– 2 x A4 sheets of paper

– scissors, pencil, ruler

– paper serviettes

– tape

– chopping board

– vegetable knife

– cloths

– peelers

– foil baking tray

– plate and bowl for microwave cooking

- Equipment for the group:

– Microwave

– Oven

- Instructions (optional)

What You Do

Introduction

- This is a Masterchef style lesson where pairs of students are all given the same ingredients, equipment and time to prepare a dish. At the end of the lesson an invited guest or guests (e.g. the principal, a senior student or parent) will judge the dishes to find a winner and runners-up.

Have photos of kūmara dishes as inspiration.

- Prepare the work stations before students arrive (see above list). Organise students into pairs. Explain:

This is a competition – Tohunga Tunukai. You will be working in pairs.

We are going to prepare, cook, present and eat our kūmara. Kūmara is delicious baked as chips, wedges, as a kūmara bake or whole. Here are some pictures of kūmara cooked in different ways to inspire you.

These are your instructions – listen carefully:

– You will be working in pairs.

– The things you can use are laid out at work-stations.

– Here are the rules:

- You must work in pairs.

- You must cook the whole kūmara.

- You can peel it or leave the skin on.

- You can use either the microwave or the oven but not both.

- Don’t use the foil trays in the microwave.

- You can use any or none of the flavourings: garlic flakes/2 herbs/2 spices

- Use the cardboard and/or paper and the paper serviettes to make something to serve the kūmara in.

- You must have shared the work equally between you.

- Consider these three things:

– Smaller kūmara (or pieces) cook faster than bigger ones. Think about the cooking time and how long you have to complete the challenge.

– A little oil will help the kūmara not stick to the pan.

– Make sure you think about how you’re going to present it before you start cooking.

– Taste everything before you serve it. It might look nice but taste terrible.

- There is a time limit. You will have 45 minutes to cook the kūmara, make the serving container and present your kūmara to me/us for judging. Your time starts now!

During the cook

- While the students are cooking spend time with each pair asking them questions that will help them focus on the task, plan ahead, time manage and solve potential or actual problems. Here are a few ideas:

– What are you cooking today?

– Do you have enough time to do that?

– Would it be better to use the microwave or the oven?

– Who is doing what?

– Have you thought about how you are going to present your dish?

– Have you tasted it?

After the cook

When the time is up, have the students bring their dishes up in pairs for tasting and judging. Be positive and encouraging – remember we want them to enjoy cooking. After judging have the students put all their dishes on a table you have decorated for a communal kūmara feast.

Suggestions

This is Māori Masterchef – many of the students will have seen the programme, so get into the spirit of a televised cooking competition. You could:

- Provide matching aprons.

- Make a big cardboard logo for the classroom.

- Invite some guest judges to join you, perhaps a parent and another staff member.

- Make sure they can all see the clock.

- Have a food/cooking related prize/s ready.

- Print participation and winner certificates.

- Have fun!

As an alternative, you could organise students into groups of four, where two are the cooks and two film the process. At the conclusion you could edit each group’s work into a “show”.

He Huatau Aromatawai

Students can:

- Listen to and follow instructions.

- Work cooperatively complete their dish.

[1] http://eng.mataurangamaori.tki.org.nz/Support-materials/Te-Reo-Maori/He-Manu-Tuhituhi-resources-available-as-PDFs